At the start of the month, I responded to the European Commission’s Open Digital Ecosystems Call for Evidence consultation. While I was looking forward to replying and giving it my all, in the end, client work and business priorities crowded out my plans a little. I am determined to contribute to more policy responses this year: it is an area of work I love. But for my business, I have to focus on what pays my team. I’m also 55 and have to consider a worklife balance. I love my business and am always happy with doing the extra hours here and there, as my work is very purpose-driven, so I can wake up every morning and be excited about what I am contributing. Perhaps I am not as fast a writer or as prolific as I used to be, and I also want to devote time to my fitness, spiritual practice, friends and family. I say all of this because my response had more of a personal tone than a business policy response as it meant I could write it faster, although perhaps that is a good thing.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on the approach I took and on the proposals I make. I now have a community feedback area on usecommune.com where you can comment directly.

/

While this is a personal newsletter effort, i did respond from my business, Platformable, but i think it’s worth sharing here. If you would like to see the version with the footnotes and references, you can read it here.

Responding to the EU Commission Call for Evidence on Open Digital Ecosystems

Platformable welcomes the opportunity to respond to the call for evidence on “Towards open digital ecosystems”. We work with enterprises, SMEs, startups, industry associations, standards bodies, and non-profit organisations on open digital ecosystems in which everyone can participate and co-create their own value. This work has included projects supporting ecosystem development with World Bank, World Health Organization, Member State health authorities, traceability of supply chain industry associations and standards bodies, International future of software technology conferences, open banking and open finance enterprises and scale-ups, and agrifood industry standards bodies.

Our definition of open digital ecosystems

While the call for evidence is laudable and it is exciting to see European policy recognise the value and importance of open source technologies, we believe a definition of open digital ecosystems extends beyond open source technologies.

Our definition is based on academic literature, global and European industry practices, grey literature, and experiences with industry and non-profit associations:

An open digital ecosystem is a network of stakeholders (including multilateral organisations, governments and regulators, standards bodies, industry associations, enterprises, SMEs, data and digital tools and service providers, researchers, nonprofits, community organisations, and individuals) that are able to co-create, collaborate, complement, coordinate and/or compete with each other equitably by using digital public and shared infrastructure, and common components and interfaces (including APIs, open standards, open data models, user interfaces, and open source technologies)

An open digital ecosystem as described above recognises the centrality of of open source technologies alongside open standards and open data models, open APIs, open source AI components, digital public infrastructure like payments rails and identity, cloud infrastructure, web browsers, and so on — all in service to enabling market operations and to ensure the production of benefits and values that support society, local economies and the environment (in line, for example, with the Sustainable Development Goals or with European core values).

It is notable that the call for evidence does not actually give a definition of its own for open digital ecosystems. It jumps from open digital ecosystems in the title of the consultation to then discussing the “open-source sector” and notes “a very active and rich ecosystem of communities of open-source developers, among the largest worldwide, whose work is well aligned with EU digital rights and principles.” One initial step the European Commission could take would be to define what it means by an open digital ecosystem.

Given the direction of the call for evidence, we will predominantly focus our response on open source, but we believe there are some limitations to the “open source ecosystem” lens. We think it is more valuable to consider open digital ecosystems on a sectoral basis.

1. What are the strengths and weaknesses of the EU open-source sector? What are the main barriers that hamper (i) adoption and maintenance of high-quality and secure open source; and (ii) sustainable contributions to open-source communities?

Europe is home to a large number of passionate, open source developers, maintainers, strategists and adopters, although there is a need for a survey instrument to calculate the size of the open source community across Europe. Commercial products from Europe often provide an open source option, which significantly helps startups and small businesses to compete internationally at minimal operational cost. For example, at Platformable, we have used the French-based Strapi open source content management system.

Europe is fortunate to also have a sizable number of open source cloud providers including OVHCloud. OVHCloud has a generous startup credits program which is allowing us to build faster and maintain more products and digital services without cost.

However, one challenge we see for European based open source cloud providers, and for the open source software that could be offered to be installed on their infrastructure is that ecosystem effects are not leveraged on these cloud provider platforms.

Amongst several US cloud providers, there are often 1-click install options that make it easy for businesses to adopt open source technologies within their cloud services without significant DevOps costs and expertise. Competing against these established players by offering a similar installation option to ease adoption amongst European cloud providers and open source technologies can be a burden. It takes time and resources to build these 1-click installation options. There are multiple ways this could be fixed:

Instead of static directories like European Alternatives and EuroStack directories from EuroStack and Digital SME Association, a two-sided marketplace could be built so that users could select the cloud provider they are using, and the open source software they want to use and then use a one-click-type functionality to install that software into their cloud service. The European Commission could help encourage open source adoption by supporting the creation of this type of marketplace.

Alternatively, the European Commission as part of its work to support adoption of European open source, could assist European-based cloud providers to build these 1-click installations. This would also help European cloud providers “catch up” to US cloud options in this area. This could be done through challenges, incentives, or other mechanisms.

One of the key shortcomings we see is the lack of a fully-rounded open digital ecosystem systems-thinking approach. This limits open source stakeholders from identifying partnerships (like those cloud providers they could partner with on one-click installations); from aligning with regulations and adopting key industry standards; and from building features for new markets.

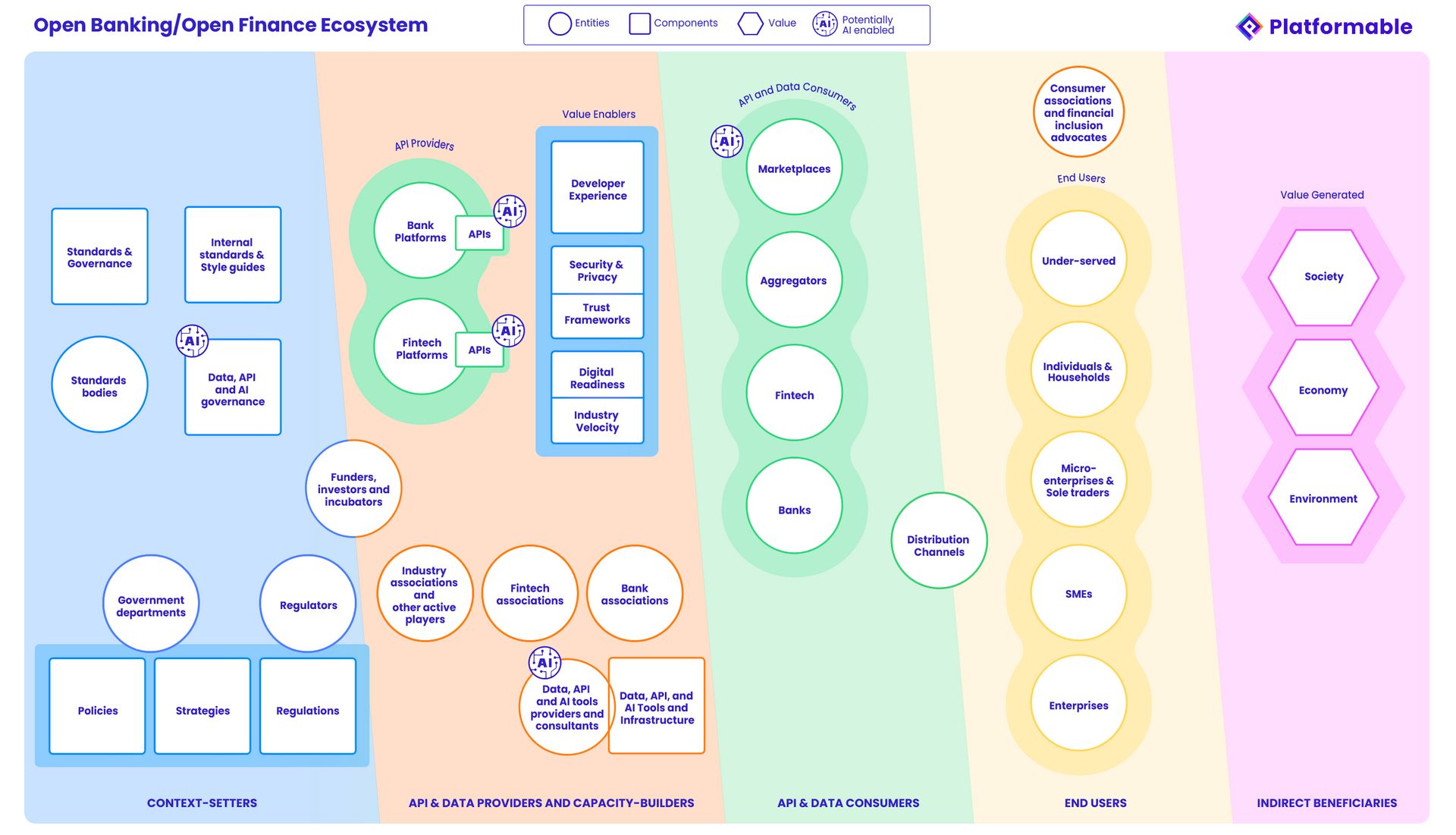

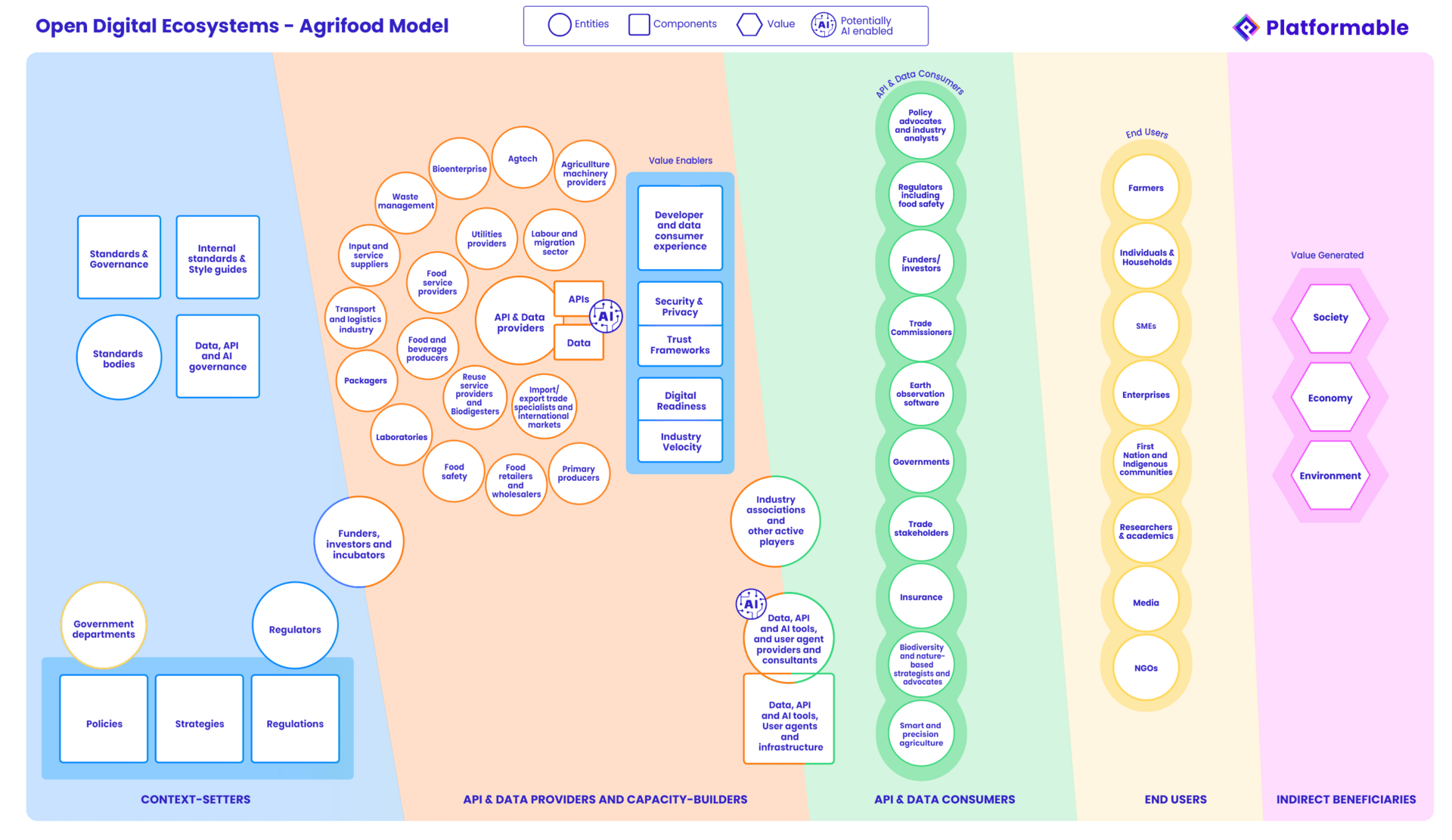

For example, we have developed open digital ecosystem models for key sectors. Open source technologies are grouped under Data, API and AI Tools and Infrastructure in each of these models, but an open digital ecosystem also recognises open standards, open data, open data models, and open APIs. These components would all interact and be used to varying degrees by entities across the ecosystem models presented.

Open Banking and Open Finance

Digital Health

Traceability and Sustainability

Agrifood

General digital ecosystems

Taking an open digital ecosystem planning and strategic approach would help open source software providers identify:

What barriers and opportunities may affect adoption

Who they can collaborate with

Their potential positive and negative impacts

The role of standards and regulations.

While this is done at a sectoral level, it can also be done at a member state or local level to identify finer grain opportunities that align with local regulations and standards. It can even be done in sub-sectors, for example, looking at the open digital ecosystem for payments (not the full open banking/open finance ecosystem) in Belgium, for example. This would provide useful insight for open source digital wallets to understand where they could enter the market or adapt their features to meet a payments use case, and so on. Future governance of open digital ecosystems needs to be sectoral. Current approaches to mapping ecosystems focus on investment or local startup ecosystems, rather than encouraging the alignment between regulations, standards, tools and open source technologies, datasets, and partnership opportunities.

The European Commission should also use these or similar models to identify metrics that identify the growth and impact of open source technologies on market viability, growth, community wellbeing, local economic resilience, and sustainable resource use.

For example, using this ecosystem mapping model, it is easier for open source technologies to identify future opportunities in:

Building open source solutions for secure research environment platforms within the European Health Data Space Health Data Access Bodies infrastructure

Aligning with the emerging global UN Transparency Protocol when building open source technologies to meet Digital Product Passport needs, or

When building data collection instruments that align with the European Union Deforestation Regulation (a role that GIZ and the International Trade Centre have had to take on to address this gap).

The European Commission could also support European-based open source to partner and work with European cloud providers by providing incentives or tax rebates of some kind (discussed below under financial issues as well). For example, potentially valuable open source software like ONLYOFFICE, based in Latvia and offering a mature Microsoft and Google workspace alternative uses AWS Cloud if using their open source in the cloud. Similarly Penpot, a Spanish-founded alternative to Figma is on AWS Cloud if using their cloud-hosted open source option. International open source of note like Plane, which potentially could have a sizable European user base, at present only offers AWS Cloud as the cloud-hosted option.

As a small business, we have had to prioritise a limited suite of self-hosted open source options and opt for cloud-hosted open source to reduce our developer workload, but that means we are back on US big tech as an infrastructure layer. The German-based OpenProject open source software provides an option for users to select between the French cloud provider Scaleway and AWS if choosing the cloud-hosted option. Open source software offering cloud-hosted should be provided a rebate or tax incentive if supporting European-cloud options to their users.

2. What is the added value of open source for the public and private sectors? Please provide concrete examples, including the factors (such as cost, risk, lock-in, security, innovation, among others) that are most important to assess the added value.

Some of the added values of open source technologies that we are aware of includes:

Sense of purpose and contribution for businesses such as mine in using open source and contributing to maintaining open source projects

Faster product development as we are able to draw on open source frameworks, standards and tools to speed up our own products and service delivery (as we have done with using Strapi as our CMS for example)

Better sustainability of IT, as we are using open source that has been developed and refined by multiple contributors, and instead of then resulting in bloated code that takes more compute and energy resources, we understand that we are able to use technologies that are widely often considered to have up to 4X performance advantages

Faster professional development and skills growth for our team members as they can see the code and understand from others how to build solutions for specific use cases.

3. What concrete measures and actions may be taken at EU level to support the development and growth of the EU open-source sector and contribute to the EU’s technological sovereignty and cybersecurity agenda?

There is insufficient training, resources and support to adopt a systems-thinking approach to open digital ecosystems in this manner. There are also financial disincentives.

One idea could be to extend the role of digital business hubs in each Member State and European city to develop this expertise. For example, in Barcelona we have BCN Activa to support startups that could extend to include expertise on open source business models and community building. Alternatively establishing a network of open source resource hubs across Europe could be developed. It is recommended that these hubs include some co-working spaces, as many open source maintainers are working in isolation and face significant risk of burn out because of the isolating, under-appreciated nature of their contributions.

A body like the European DigitalSME Association could be encouraged to develop an open source mentoring and support program.

One of the biggest needs in this area is for business models expertise. Open source should not mean free. There are several business models that are used by open source technologies including:

Enterprise pricing to provide the open source technology with 24/7 support options and input into feature development

Free open source community editions for self-hosting and paid cloud hosting options

Tiered pricing that provides a basic open source functionality vs premium paid options with additional features

Paid complementary tools, support packages, templates, and other digital products and services to users

Sponsorship and donations.

However, there are limited supports available to open source entrepreneurs to understand the potential and suitability of each of these business models for use in Europe, in their member state, or for their industry segment.

In Spain, for example, there is no recognised legal or taxation structure that understands open source. So are donations/sponsorship for a free service calculated as income? Even though a product is being provided for free to Spanish businesses that then use the software to generate economic opportunities? What if there is a free level of service provided by an open source company to its clients, but the client pays for a premium service? There is no deductible for the contribution to the economy from the open source basic layer. This can create challenges in Spain for funding recipients to European Commission open source grants: how do recipients accept the grant as a contribution to the open source and not as personal income?

Businesses adopting open source, particularly European-built open source, should be eligible for a reduced tax rate if they show a contribution to the open source they are using. For example, we understand there are Spanish-based open source technologies that are widely used across Europe, for example, in Irish universities, but without any financial incentives, they make no contribution. This is in contrast to US-based businesses that recognise the value and importance of the open source technology to their value chain, and contribute sponsorship monies to European open source initiatives (which then have to be declared annually as personal income as there is no other way to receive these payments, and then get taxed at the full rate for the income). Approaches such as those outlined in the EuroStack’s Buy European initiative could be applied to open source.

We believe the new 28th regime being proposed should define an open source technology option that adequately describes taxable components and non-taxable/deductible components that businesses operating across Europe could apply. To ensure that this was not “gamed” perhaps those applying for this organisational status would have to achieve digital public goods status, or only those open source technologies that apply a specific, approved open source licence or have a specific size community can apply for recognition for tax or financial incentives.

Expertise and support in fostering a community of maintainers and contributors is also needed for open source technology creators.

We also hear of large enterprise sectors such as education feeling cautious about implementing open source technologies, however, this appears as an individual choice, as many did not have a problem suddenly integrating US AI providers into their education models. This also appears to have happened in digital health sectors where adoption of US AI tech, especially OpenAI, appears to have been done outside any transparent procurement processes. The European Commission should seek to provide incentives and supports, in some of the ways described throughout this response, to support industry stakeholders to adopt open source technologies. Assistance with compliance, audit, and security review may need to be provided to overcome obstacles in some sectors.

Recently, there have also been a number of scams that affect the reputation and community of open source providers. There are instances in Europe where a crypto “memecoin” has been created using the name and logo of an open source software with explanations given that this would support the open source creator/maintainer, but created in fact by someone not attached in any way to the community or technology. These scams target the open source community of contributors and adopters. Open source technology creators are then stuck in a difficult situation: they need to alert their users that this is not an official financial mechanism, but also want to avoid promoting the memecoin in case it creates a Streisand Effect.

4. What technology areas should be prioritised and why?

Browsers and other agents and the infrastructure layer, especially cloud service providers, need to be supported to achieve real autonomy and digital sovereignty for Europe.

European-focused open source AI components could also be prioritised as this is an area where significant enterprise investment is focused at present and as a result, US tech options are being embedded into European infrastructure, creating cybersecurity, data sovereignty and production risks.

More importantly Europe needs to ensure it has options to offer digital alternatives to AI. AI has not yet proven itself to be evidence-based for much of the intended use cases currently being implemented globally, has limited data on its true benefits and accuracy, can be energy-intensive and may not prove to be sustainable or affordable in the mid-term. Having open source digital technologies that were not reliant on AI is an important resilience and future competitiveness factor for Europe.

We also believe Article 6 of the Copyright Act should be repealed across Europe to ensure a level playing field for European tech including open source technologies.

5. In what sectors could an increased use of open source lead to increased competitiveness and cyber resilience?

We believe the following sectors should be prioritised for both competitiveness and as critical sectors requiring priority focus and support.

Banking and finance: In particular, open source opportunities for payments and identity rails should be encouraged to support the continued roll out of Third Payment Services Directive, Digital Wallets and Instant Payments regulations. European based AI will also be vitally important here with the current rapid adoption of agentic commerce and growing interest in stablecoins requiring European open source alternatives to be developed rapidly.

Digital health: In particular, technologies that can support the European Health Data Space initiatives and that can overcome the current non-transparent adoption of US-based AI in healthcare should be prioritised. More global pandemic open source tools like Epiverse will also be needed in future, especially those that address climate health impacts.

Traceability of supply chains: To align with the work of the UN Transparency Protocol, the growing global book and claim and carbon market sectors, and Digital Product Passport agenda, there are multiple opportunities for open source technologies to develop new technologies for this emerging sector.

Agrifood: To accelerate the work of FIWARE and the Agrifood Data Space, new open source technologies at scale are needed to ensure resilience and farmer and producer economic stability.

Please join me on Commune to join a conversation about this newsletter. Next month we will look at the json.api created for our tech stack (thanks Kin!), and describe the rest of our migration to European and open source tech. Please share this edition with anyone who might be interested and thanks for subscribing.